Rouge Valley Conservation Centre

Rouge Valley Conservation Centre

Architecture

By George W.J. Duncan

The Pearse House, a Rouge Valley landmark. Well known to the many visitors of the Metro Toronto Zoo, this classic Ontario Farmhouse, with it’s colourful brickwork hidden beneath a coat of whitish paint, is the key to a fascinating chapter in the Rouge Valley’s history.

With its steeply-pitched centre gable and balanced front, the Pearse House is a late example of a Classic Ontario Farmhouse. The smaller, earlier cottage, built about 1869, forms the core of the 1893 farmhouse.

The part of the house which dates to circa 1869 is most easily seen in the north-west section of the cellar, where the compact rectangular shape of the original fieldstone foundation and heavy construction of the first floor readily distinguishes this area from the later additions.

The original house was a one-storey, frame structure, clad in board and batten siding. Portions of the exterior walls of the earlier building, showing doors and windows that were blocked up during the extensive later changes, can be seen beneath the interior board sheathing on the north and west walls of the north front room.

Although some of the circa 1869 cottage remains, the Pearse House, as it exists today, is essentially a Late Victorian, balloon-framed, brick veneered building of 1893. With its 1920’s sunroom and earlier core, the house is a fascinating record of a pioneer family’s evolving needs, fortunes and tastes from the 1860’s to the 1930’s. Its characteristic farmhouse plan is T-shaped, with a rear kitchen wing.

The design of the Pearse House is remarkable for its steeply-pitched, six gabled, dramatic roof line, its unusual patterned brickwork and its ornate Victorian “gingerbread” front verandah. Although the design follows a somewhat earlier architectural tradition, the tall, narrow, large-paned windows and the use of wire or “round” nails in much of the construction represents what was up-to-date building technology towards the end of the 19th Century.

The colourful patterned brick treatment, the most significant architectural feature of the house, is hidden under a coat of whitish paint. On a background of buff-coloured or “white” brick, red brick was used to create decorative accents on the corners, known as “quoins”, arches over windows and doors, known as “voussoirs”, a slightly projecting base to the walls, know as a “plinth”, and banding below the level of the eaves in a repeating cross pattern.

Patterned brickwork was common in this part of Ontario from about 1850 to 1890, but the particular design used on the Pearse House is distinctly different from other examples remaining in the area because the quoins are twice the usual size and are non-alternating and non-continuous.

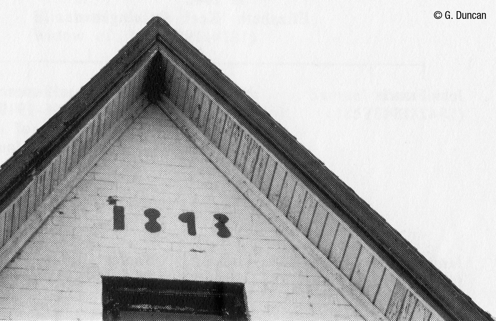

The date “1893” is clearly seen in the north gable of the kitchen wing, worked into the brick by the builder. The Pearse family must have been proud of their new home, marking the date of this important achievement in the history of a pioneer family for later generations.

On the front verandah, the extensive use of machine-made decorative woodwork displayed on the on the spoolwork posts, fretwork brackets and pierced frieze epitomizes the technological advances of the Late Victorian period as applied to even a relatively modest rural residence. Similar verandahs once existed on the north and south sides of the kitchen wing. The north verandah has disappeared along with the frame summer kitchen and woodshed, and the south verandah has been replaced with a many-windowed sun porch, typical of the early 20th century.

The interior of the Pearse House, now stripped of its plaster and mouldings, was once trimmed with ornate Late Victorian woodwork, made from pine but paint-grained to simulate oak. In the main front rooms of the ground floor, the one-foot high baseboards had boldly moulded edges and reeding. Door and window casings had symmetrical profiles and bull’s eye corner blocks. Scraps of earlier, simpler mouldings found within the structure of the house may have been salvaged from the original cottage.

Front Verandah Detail. The intricate woodwork displayed on the verandah epitomizes the technological advances of the Late Victorian period. Beneath the peeling paint, the wood is actually very well preserved.

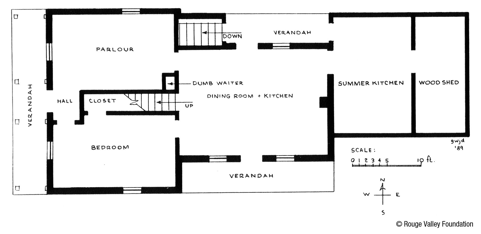

The floor plan in the front part of the house consisted of a small, central “box” hall, off of which the large parlour and dining room were reached. In later years, the south room, which was perhaps the original parlour, was used as a bedroom for the aging James Pearse Jr. The dining room then became the parlour and the dining room use was combined with the large kitchen. Upstairs, above the front section, there were three bedrooms and a centre hall. The old stair rail, with its turned newel and balusters, is still found in the upstairs hall. In the rear kitchen wing, there was a large, single room both upstairs and down. A dumb waiter, a type of small elevator designed to bring food upstairs from its storage space in the cellar, was located on the wall of the kitchen that adjoined the main house. A brick chimney was later built into the dumb waiter shaft when a furnace was installed.

Interestingly, the kitchen wing appears to have originally been constructed as a separate building, with its roofline raised and placed in its present position at the time of the 1893 expansion. It may have been an earlier addition to the Pearse House that was reoriented to tie in with the final plan for the “new” house.

An early photograph from the Pearse family collection shows a low, one storey, hip roofed cottage with a large one-and-a-half storey addition. This addition likely dates to the 1880’s and is almost a separate house in itself. There is some doubt as to whether or not this photograph indeed shows the pre-1893 Pearse House, but if it does, the addition must have had the proportions of its windows altered and the height of its roof raised to conform with the appearance of the kitchen wing as it exists today.

If the photograph is of another building altogether, it at least illustrates the practice of 19th century homeowners in expanding and improving their modest early dwellings in a similar manner as the employed by James Pearse Jr. in his Rouge Valley homestead.

Ground Floor Plan of the Pearse House. This plan is based on the reminiscences of Mrs. Elda (Pearse) Skidmore, granddaughter of James Pearse Jr. Of particular interest are the now demolished summer kitchen and woodshed and the “dumb waiter”.

Expanding the Homestead. This early photograph from the collection of the Pearse family may or may not be related to the James Pearese Jr. House in its pre-1893 form. It does, however, show how 19th century homeowners expanded and improved their dwellings over the years, much in the same manner as James Pearse Jr. did. Note how the gable wall of the one-and-a-half storey house is constructed of rough sheathing, in anticipation of a future second floor being added to the single storey, earlier cottage.

Pearse House History (continued)

To donate to the Rouge Valley Conservation Centre click on the button below:

Click here to see photos of the Pearse House’s transformation into the Rouge Valley Conservation Centre.

Kids Programs

Special Events

Donate

About Us

Rouge Valley Conservation Centre © 1995 – 2012 All rights reserved